The Wwise Interactive Music Symposium, held at the Canada Water Theatre, brought together composers and leading professionals from the film and video games industries. The day was a deep-dive into the future of interactive music with talks from composers who are pioneering the use of interactive music now.

Music to my Eyes: Crash Course on Interactive Music

The first talk was given by Simon Ashby (VP Product and Co-founder at Audiokinetic) and was a history lesson in the world of video game music. He discussed the capabilities and limitations of previous games consoles. We were introduced to a theory called “voice stealing” where the sound effects of a game would be given a higher priority and take over the music completely. This is how game audio was done on consoles with very limited channels. I’m glad this isn’t something we have to take into consideration when writing music now. We still have to make sure that dialogue and sounds effects are audible over our wonderful scores but that rarely means having the music cut out altogether.

“Creativity comes from limitations.” – Simon Ashby

Beyond The Linear – Approaches To Interactive Music Design And Implementation

The 2nd talk of the day was by Ciaran Walsh (Composer, Sound Designer and Audio Programmer at Hornet Sound). Ciaran walked us through some real-world examples of non-linear music being used in games and showed us techniques we could use to approach our next interactive music projects. Using Wwise as the middleware, he explained that music transitions based on game states and story events and that it’s up to use to decide the transition rules. The challenge happens when figuring out how to write 2 hours of music and stretch over a game that can last between 12 hours and infinity ∞. This is when we were introduced to music variability ideas.

Music Variability

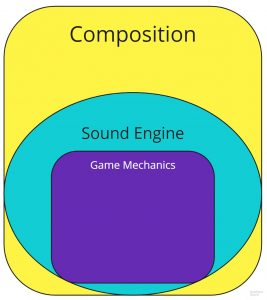

As composers, we can’t write an infinite amount of music so we need to come up with clever ways to reuse our music so that it doesn’t become repetitive for the listener. When it comes to composition, Ciaran warned us to stay away from patterns and obvious loops. That 2-bar drum loop you love will get annoying after about 30 seconds. We can change things up by playing with things like the tempo, rhythm, time signature and instrumentation.

Once we’ve got our music recorded, we can get creative with the sound engine and game mechanics. Wwise lets us use game data to modulate our music in real-time. Using things called switch containers, we can attach any part of our music to a game state or RTPC. This is completely dependent on the type of game you’re working on but you could link your music to something like “threat level” or “weather”. Something I hadn’t thought about before was using Wwise to mimic musical forms like Rondo, Sonata or even a 12-bar blues.

“The music should be as complex or as simple as the game needs.” – Ciaran Walsh

Real-world Examples

We were shown a few real-world examples so we could see everything in action.

Fractured Space – This game was in open development which meant it was live while it was being actively worked on. This provided a challenge to the composer as the temp music had to go live too and there’s always a chance that the listeners will fall in love with it. They used a state system in Wwise for the music in Fractured Space and had all the music in one container. This switched based on the situation you were in a was able to transition smoothly into cutscenes using Wwise’s automatic crossfade.

So Let Us Melt – This is a Google Daydream VR game with music written by the wonderful Jessica Curry. The music is the star of this game and most of it is actually linear. Wwise was used to trigger musical phrases on top of a looping musical bed. Ciaran’s analysis of this technique was that a musical bed must be simple and the complexity and interest should come from the triggers.

Orchestral Manoeuvres: Tips For Successfully Recording Your Interactive Score Live!

We were treated to our 1st panel of the day! Moderated by John Broomhall (Composer, music artist, commentator & Game Music Connect co-founder), the speakers were Alastair Lindsay (Head of Audio, Worldwide Studios Europe – Sony Interactive Entertainment Europe), James Hannigan (Composer and founder of Screen Music Connect) and Allan Wilson (Conductor, orchestrator, arranger & music consultant).

Get interactive but don’t overcook it.

The panel focused on budgeting, to begin with. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you want and budget higher than what you need. The list of things you have to arrange and pay for when organising an orchestral recording is staggering. Here’s an overview of just how many people are involved:

Orchestrator/arranger, conductor, professional music prep person (the orchestrator will usually arrange this), musicians (you could have 80 at a time!), specialist players, sound engineer (often a person of your choosing), the studio itself, travel arrangements, etc. This is not a small list and I’m sure there are many I missed off. When creating an effective budget, you need to budget separately for each one of these groups, add it all together and then ask for more. Put it all in a spreadsheet and save it as a template.

A really eye-opening piece of information from Allan was just how much music you could expect to record in a session. In London, you can expect to record 8 minutes of music per hour. Obviously, the number of cues affects this a lot but the best advice was to record lots of cues in a single DAW project session so you don’t need to keep wasting time loading up new sessions. Fable Legends had 350 cues and 220 transitions. A new Pro Tools session for each one of these would have wasted so much time.

While I might think my MIDI orchestral score sounds good, it might not actually be playable by a real orchestra. I learned that a great orchestrator can add a lot of expression to your music. They really focus on the detail and making sure it’s ready for the orchestra to play. They might even double some instruments to add colour. Another thing that either you or the orchestra can do is to make the score super clear. You might do this by adding text explaining that this is part A or this is a fight scene. Giving the orchestra context and making things clearer can save you a lot of time and money.

Finally, a composer should stay in the booth and produce the music. Let the conductor conduct. They’ll relay any troubles you might be having to the orchestra and will be able to guide the musicians through recording parts again with diplomacy. They’ll also have an intimate knowledge of the orchestra so can suggest in which order cues should be recorded in to keep everyone fresh an happy. Reading the room and politics are important to a recording session so you will want to leave it up to someone who knows what they’re doing.

Music for Games Should be More than Just Music

View this post on Instagram

We had the pleasure of listening to the composer Olivier Deriviere for this next talk. The first thing he did was to break down the relationship between a composer and the game developer. The composer is simply a service provider and the developer is shipping a product. It’s proven to be a very effective relationship but it’s also very business-like and stale. Instead, Olivier said we should:

“Envision together the game through a musical spectrum.” – Olivier Deriviere

Share a vision! The dev will probably doubt it at first but if you can get them to imagine and understand your vision then you’ve sold it. It’s your job as a composer to help them understand it. We looked the usual approach of working with a developer first and understanding the game world, story and game mechanics. Then Olivier took it a step further and suggested that on top of that we needed to do a few more important things:

- Add meaningful music and extend the artistic vision of the game

- Improve our craft to push the boundaries

- Compose for the game. You might not be a safe choice but you are the right choice.

- Create music that’s in service to the game.

After detailing how to start working with a developer, he then went on to show some examples of music he’d written for games. Memories Retold had 2 main characters; a German man and a younger Canadian boy. He linked these characters by writing music in the relative major/minor of each one.

The next game he showcased was Vampyr. After talking a lot with the devs, he decided to choose 3 main states that music would react to. Those were outside, inside and whether you were in conversation with an NPC. Music outside was lush and full of reverb to reflect the open world aspect of the game. Inside, the music became more intimate with softer pianos and less reverb to make everything feel close. Whenever dialogue started, the music would switch from including a high sounding cello to focus on a low cello with fewer sounds. The reason for the low cello was to leave room for the dialogue audio to sit in the mix.

Lastly, we looked at a game called Get Even. I think this was Olivier’s most ambitious project yet. He embraced the wildness of the game and pushed the boundaries of audio by implementing things like having all “room tones” be in sync both harmonically and rhythmically. He was quite happy to build the music up and make it incredibly tense and almost unbearable. The character in the game knows he’s about to die so the unbearable music actually serves the game there. Some of the music was also diegetic and would play out of various radios dotted around the map with the rhythm and lyrics changing after a certain trigger in the game. The complexity of having the music and sound effects all work together was astonishing.

Music is not just music. It’s skilled professionals using their craft to envision music as an asset. It’s meaningful to its own purpose and is there to serve the game at the same time. And finally, Olivier told us that music for games is a language yet to be created. I loved this part the most as it reminds you that there really are endless possibilities in this new medium of video game music.

A Composers Guide To Business Affairs

This was the final panel of the day. Moderated again by John Broomhall, the panel included Richard Jacques (Composer, music rights advocate (BASCA, PRS), Chair: Ivor Novello Awards), Tom Weller (Strategy Manager, PRS for Music), Alastair Lindsay and Darrell Alexander (Film, TV & Games Composer Agent, CEO of COOL Music Ltd and The Chamber Orchestra of London).

I’ll be very brief on this talk and keep it as simple as “know your rights”. When you create something as a composer, the rights are yours and it’s up to you to negotiate and sign them over if you wish. There are so many different deals out there that it’s hard to say what’s the best one. It changes for every game depending on budget, relationship and a whole host of other variables. A good deal would allow you to release the soundtrack later on and earn royalties from it. Games can fade out of existence, especially with the turnover of consoles but fans love game soundtracks and you’ll find lots of them available to stream on Spotify. Make sure the fans can get to your music and make sure you get a cut of that too!

The evening ended with some food and drink kindly provided by the organisers. Thank you to John Broomhall and Audiokinetic for putting on this great event and giving us all the chance to hear all the talented speakers.